Project Description

Abstract:

Our project parallelized genetic algorithms in the BoxCar2D simulation to optimize 2D vehicle design, using the MPI framework in a master-worker setup. Experiments on the Perlmutter computing clusters demonstrated significant performance improvements, with the parallel implementation reducing runtime from 64.72 seconds with 1 processor to 2.49 seconds with 63 processors. The parallel approach efficiently explored the design space, quickly converging on high-fitness vehicles with optimal configurations. Despite increased communication overhead with more processors, the overall reduction in computation time and enhanced design exploration confirmed the efficacy of our parallel implementation.

Introduction:

Many computational design problems involve searching large, complex spaces for suitable solutions. Genetic algorithms (GAs) are a popular method for efficiently navigating these spaces by mimicking natural selection, mixing and matching the best solutions to evolve better ones. GAs manage a population of individuals, each encoded by a genome, to evolve individuals with the highest fitness. The process starts with a randomly generated population, then evaluates each individual, performs crossover on the best individuals to mix genomes, applies mutation to introduce diversity, and repeats until a sufficiently fit individual is found.

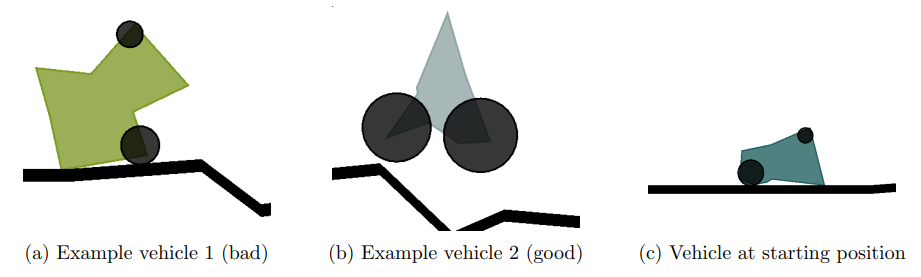

BoxCar2D is an online tool that visualizes genetic algorithms in real-time. It starts with a randomly generated population of 2D vehicles with wheels, evaluates their performance on a randomly generated terrain, and iterates through crossover and mutation processes to evolve better vehicles. The website allows users to tweak parameters and vote on the best designs. Examples of different vehicles, including a good and bad one, are shown below in figure 1.

Figure 1. Example vehicles in various configurations and terrains

My team’s project aims to parallelize the genetic algorithms via the BoxCar2D simulation. Using an existing open-source implementation, modifications were made to the Box2D physics and world code to create a baseline serial implementation for comparison with parallel versions. Various parallel genetic algorithm (PGA) topologies, such as global single population, grid, and ring topologies, are explored for enhancing the simulation's performance.

Methods:

Parallel processors can significantly speed up genetic algorithms (GAs) by efficiently partitioning large populations. The parallelization step varies with the problem type, as different steps require varying computational efforts. For design problems needing physical simulation, like BoxCar2D, the most significant performance boost comes from parallelizing fitness evaluation.

There are two main PGA types: global single-population master-worker and multiple-population. The master-worker type involves a master processor handling GA steps and distributing fitness evaluation tasks to other processors. Multiple-population PGAs assign each processor a population, with inter-island individual trading during GA steps. Our project focuses on the master-worker method, where each processor simulates a given vehicle genome and reports the fitness score back to the master processor.

To parallelize the C++ implementation of BoxCar2D, the MPI framework was used in a global single-population master-worker style. The master processor managed the overall population and assigned each worker processor the genome of a vehicle to simulate and return a fitness score. To reduce communication overhead, only genome information was sent back and forth between master and workers. World and terrain information was established in each processor with the same seed to ensure consistency throughout all runs.

Experiments were conducted on the Perlmutter computer cluster. The genetic algorithm's fitness scoring was based on the distance traveled by a vehicle. Crossover was performed using fitness proportionate selection, where higher-fitness vehicles were more likely to pass on their genes. A mutation rate of 0.05 was used to maintain genetic diversity without premature convergence.

Results and Analysis:

We observed a significant performance boost by scaling the population size and the number of processors in our project. The data and figures in the study clearly show that larger populations significantly enhance the ability to explore the design space, leading to quicker convergence on high-fitness vehicles. Notably, the parallel implementation outperformed the serial one by drastically reducing the time needed to find solutions.

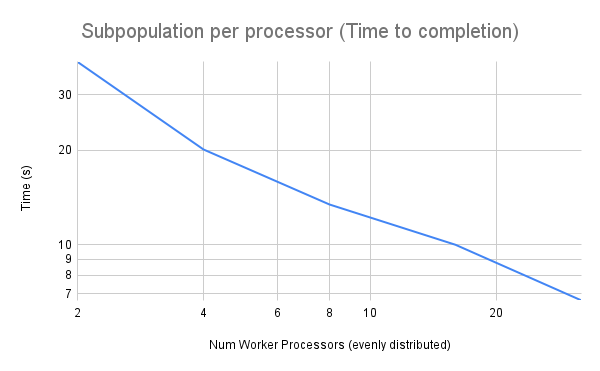

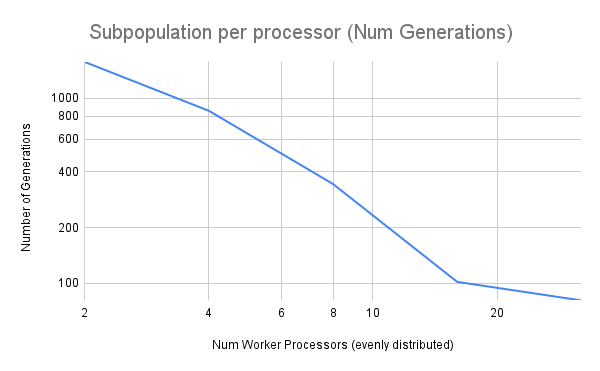

The table and figures below illustrate the strong scaling data, where increasing processor counts resulted in reduced completion times and fewer generations. For example, with one processor, the time taken was 64.72 seconds with 35,408 generations, whereas with 63 processors, the time dropped to 2.49 seconds with 121 generations. This demonstrates the efficiency gained from parallelization.

| Processors | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 63 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | 64.72 | 27.12 | 12.06 | 8.40 | 4.47 | 3.17 | 2.49 |

| Generations | 35408 | 2344 | 1109 | 607 | 193 | 164 | 121 |

Figure 2. Strong Scaling for global population master-worker PGA - Time

Figure 3. Strong Scaling for global population master-worker PGA - Generations

Regarding vehicle configurations, we found clear trends in successful designs. Vehicles with slim chassis and larger wheels were more effective in navigating challenging terrains, avoiding obstacles, and preventing high-centering on spiky hills. Even though the terrain remained constant, different body configurations emerged based on the number of processors, showcasing the algorithm's adaptability and optimization capabilities.

Figure 4. Final vehicles found by varying numbers of worker processors

Increasing the number of processors generally reduced computation time, though the extent of this reduction varied. In smaller configurations, doubling the processor count led to a runtime drop of over 50%. However, in larger configurations, the decrease in runtime was less significant, though still present.

One reason for this variation is that more processors require increased communication between master and worker nodes, as well as more synchronization efforts. In our parallel implementation, barriers were used to ensure all worker processors completed their tasks before the master processor executed the genetic algorithms, preventing race conditions. This synchronization is crucial but can lead to idle time as processors wait for others to finish, especially in larger configurations.

Despite these challenges, the overall reduction in computation time outweighed the increase in communication time, leading to improved performance. It's important to note that reduced runtime did not always equate to fewer computations. Our experiments showed that as the processor count increased, the number of generations performed in each run decreased. However, when multiplying the number of generations by the number of processors, the total computational load remained around 5,000. This indicates that while each processor does less work individually, the total computational load remains constant, confirming that our parallel implementation is achieving its goal of efficient workload distribution.

Personal Takeaways

This project significantly advanced my proficiency in parallel programming and coding abilities. While I had previously tackled assignments involving OpenMP, MPI, and CUDA for my classes, embarking on this independent project allowed me to explore parallelism in a novel context. Applying my knowledge of parallel programming to a self-designed project provided me with a fresh perspective on problem-solving. It not only deepened my understanding of parallelism but also enabled me to envision its application beyond the confines of classroom assignments.